“TTRPGs saved me,” I tell people, and I mean it without irony or exaggeration. “They’re the second or third best thing that ever happened to me—after my wife and daughter, obviously.” I pause, let that land. “I feel it’s a moral obligation, a crime even, if I can’t get as many people as possible to experience this at least once.”

That conviction didn’t arrive fully formed. It came through failure, through watching potential players walk away because I’d made them feel small, through realizing that my love for precision was building walls instead of bridges.

The Washing Machine Incident (Or: How Nervousness Makes Idiots of Us All)

Six years ago, I was a fanboy. A 6’4″, 120-kilo fanboy with an inexplicable American accent that intensified under stress, but a fanboy nonetheless. I’d spent years admiring this photographer-turned-game-designer from afar, sending perfectly grammatical emails that went unanswered, nursing quiet heartbreak over rejection.

Then one day we finally met at a mall in Bangalore. I was so starstruck, so overwhelmed by the confluence of admiration and social anxiety, that when I needed to excuse myself, my brain misfired spectacularly. “Anna,” I announced in full nasal Louisiana drawl, “I have to use the washing machine.”

The washing machine. Not the washroom. The washing machine.

He stared at me. I stared back. Somewhere in my prefrontal cortex, a tiny voice screamed corrections, but my mouth had already committed to the bit. That moment—that beautiful, mortifying collision of intention and execution—taught me something crucial: People don’t need perfect performance to connect. They need permission to be imperfect.

From Norway with Obsession

My TTRPG origin story involves prioritizing inanimate objects over my infant daughter, which sounds worse than it was but probably wasn’t great. My wife and I were in Oslo, broke but committed to traveling before our daughter turned two (free airfare, you understand). On a whim, I wandered into a game store on Kakergata Street.

“I know there are these games where you roll fancy dice and tell stories,” I told the clerk. “What is that?”

His eyes lit up with the unmistakable gleam of commission earned. Fifteen minutes later, I owned the Dungeons & Dragons fifth edition boxed set, seven sets of dice, and the absolute certainty that I’d made a crucial life decision.

The walk back was torrential. Rain hammered down like divine disapproval. I pulled my daughter from her stroller, strapped her against my chest in the baby carrier, and very carefully placed the D&D books in the stroller. Then I covered them with a poncho. Held an umbrella over my less-than-two-year-old daughter. Walked a kilometer and a half while my wife delivered a blistering monologue about priorities and parenthood.

“You have no idea,” I kept thinking, shielding those books with my body. “You have no idea what these represent.”

I didn’t know either, not really. But some instinct told me I’d just bought a key to somewhere I desperately needed to go.

The Problem Nobody Talks About (Except It’s Obvious)

Here’s what happened next: I came home, devoured the rulebooks, watched Critical Role until my eyes bled, and decided I knew how to run D&D. Matthew Mercer ran games for eight people, so clearly that was standard. I strong-armed eight Toastmasters colleagues into playing, promising them improv practice and table topics experience.

That first game with the Lost Mines of Phandelver—it was magic. Absolute magic. People who’d never rolled a d20 were suddenly declaring actions, building characters, getting invested in whether the spider eggs could be stolen and sold to witches.

But then what? They loved it. They wanted more. And I was the only Game Master within reasonable distance who could provide it. The math was brutal: one GM, infinite demand. Even if I ran games every single day, I could maybe serve thirty people well. Maybe.

That’s when I realized the hobby had a supply chain problem. We were drowning in players and starving for Game Masters. If I wanted this thing I loved to grow—if I wanted people to experience what had grabbed me by the throat in that Oslo game store—I needed to stop hoarding the GM role and start teaching it.

What It Actually Takes to Run Your First Game (Spoiler: Less Than You Think)

The mythology around Game Mastering is all wrong. People imagine you need Matthew Mercer’s voice acting range, a doctorate in improvisation, encyclopedic system knowledge, and probably a background in theater. The truth is simpler and more democratic: If you can talk, you can GM.

I’ve identified four levels of roleplaying, and every single one is legitimate:

Level Four is voice acting—doing accents, changing pitch, embodying characters vocally. This is Matthew Mercer territory, and it’s spectacular when it happens.

Level Three is speaking in character without vocal performance. “Vivian, we must open that cargo crate immediately.” Same voice, different perspective.

Level Two is third-person narration. “Vivian tells Ulu to open the crate.” You’re describing actions rather than performing them.

Level One is pure intention. “I want to convince the guard to let us through.” No performance, just declared goals.

All four work. All four create memorable sessions. The obsession with voice acting isn’t just unnecessary—it’s actively harmful because it convinces people they’re not qualified to try.

Why I Stopped Being the Grammar Police

I used to correct people constantly. Someone would say “less” when they meant “fewer,” and I’d interrupt. They’d mispronounce a spell name, and I’d provide the correct phonetics. I thought I was helping, maintaining standards, ensuring quality.

What I was actually doing was building barriers.

Every correction is a small violence. It tells someone: “You’re not good enough yet. You don’t belong here fully. There’s a right way, and you haven’t learned it.” Most people can absorb one or two of those before they start editing themselves into silence. A few more, and they stop showing up.

The day I stopped correcting grammar was the day I chose accessibility over accuracy. If someone stumbles over a word but conveys meaning, the meaning matters more. If they’re nervous and mixing up terminology, their courage to try matters more. If their character voice is inconsistent but their tactical thinking is brilliant, the tactics matter more.

This hobby—these games where we roll dice and pretend to be elves and argue about imaginary treasure—they offer escape from reality’s relentless judgment. Why would I import that judgment into the one space designed to be free of it?

The FARTS Framework (Yes, Really)

When new Game Masters ask me how to prepare for player unpredictability, I teach them FARTS. It stands for Fight, Avoid, Research, Trick, and Speak—the five actions any player can take in any scene.

Your players encounter a giant spider guarding a cave entrance. What can they do?

Fight – Attack it directly with weapons or spells

Avoid – Sneak past, find another entrance, wait it out

Research – Study its behavior, check for weaknesses, gather information

Trick – Create a distraction, set a trap, use illusions

Speak – Negotiate, intimidate, befriend, bribe

If you’ve thought through even basic responses to these five approaches, you’re prepared for 90% of what players will attempt. The other 10% is where the magic happens—players surprising you, combining approaches, inventing solutions you never imagined.

That’s when you remember: You’re not performing for them. You’re not even really running the game. You’re managing a space where their creativity can breathe.

The Cultural Paradox We Never Discuss

I’ve run the same Indian mythology-themed adventure for Germans, Canadians, Americans, Singaporeans, and Indians. The foreigners go wild for it. “Oh my God, this is so cool—tell me more about rakshasas!” The Indians? “We see this stuff in the Ramayana. Why are you making us play this?”

It took me years to understand what was happening. For foreigners, Indian mythology is fantastical—alien landscapes, unfamiliar power structures, gods who feel genuinely other. It triggers the same imaginative escape that Arthurian fantasy triggers for us. Knights and castles and green meadows—that’s exotic. That’s somewhere we can disappear into.

But for Indians, mythology walks among us. It’s on the back of auto-rickshaws. It’s in temple architecture. It’s in the stories our parents tell to teach us lessons. When we sit down to play a game about asuras and devas, we’re not escaping reality—we’re just encountering it in a different format. The magic circle doesn’t fully close.

This creates a responsibility for Game Masters. If we want to use Indian mythology, we can’t just bolt it on like toppings on a sandwich. We can’t set an adventure on a train from Calcutta to Shimla and call it “Indian-flavored” because there’s a swastika motif and someone’s wearing a turban. Culture isn’t decoration. It’s the flour in the chapati—mixed in until it’s indistinguishable from the whole.

The Oppenheimer Moment

A year ago, I became obsessed with creating the perfect dungeon. I backed a Patreon, downloaded hundreds of STL files, ran my 3D printer for 600 hours in a single month. I learned to paint miniatures. I designed lighting systems. I created a modular dungeon that could be reconfigured on the fly, each piece lovingly detailed and professionally finished.

People saw it at conventions and lost their minds. “This is incredible! We have to play this!” There were actual arguments about table access. Someone suggested I start charging admission.

And I hated every second of running it.

Not creating it—the art of making something beautiful was transcendent. But using it? The dungeon was a gorgeous cage. Players couldn’t improvise without breaking the carefully constructed geography. I couldn’t adapt to their weird ideas without destroying the aesthetic. The thing I’d built to enhance play was actually constraining it.

I felt like Oppenheimer quoting the Bhagavad Gita: “I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” I’d created something powerful that turned against its purpose.

These days, I use index cards with sharpie drawings. A generic fountain. A blacksmith’s anvil. A stone altar. I build maps in real-time based on what players need, not what I’ve predetermined they should encounter. It’s faster, cheaper, infinitely more flexible, and vastly more fun for everyone involved.

The lesson isn’t that elaborate props are bad. It’s that tools should serve the story, not the other way around. If your beautiful creation is stopping you from saying “yes” to player creativity, it’s not serving the game.

What Actually Costs Money (And What Doesn’t)

“How expensive is this hobby?” people ask, and I give them two answers.

The honest answer: You can spend your entire life playing TTRPGs without spending a single rupee. D&D’s System Reference Document is free. Pre-generated characters are free. Online dice rollers are free. Maps, music, character sheets, one-page RPG systems—all available at zero cost. The biggest investment you need to make is using your imagination.

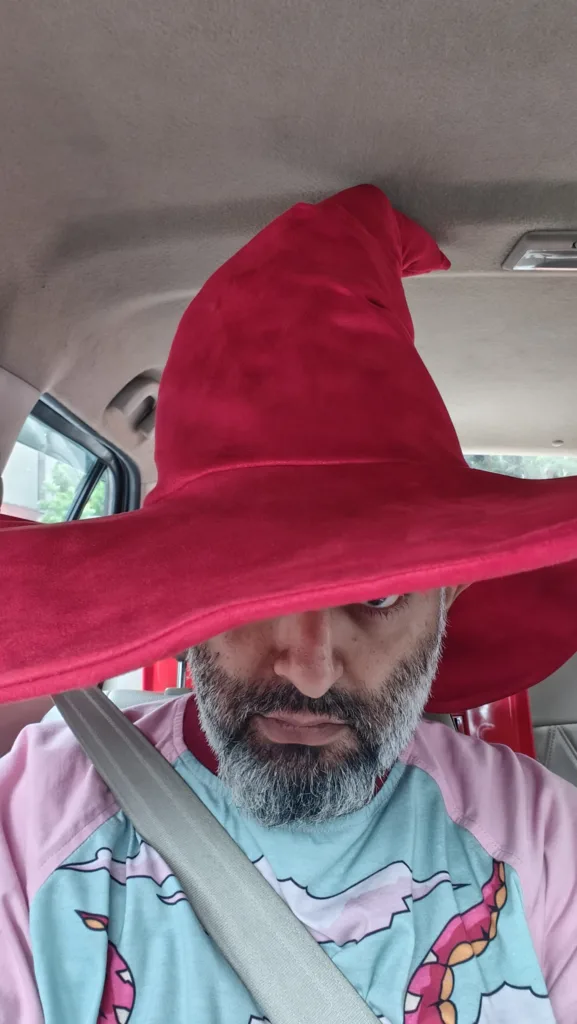

The real answer: It’s a slippery slope greased with desire and justified by passion. You’ll start with free resources. Then you’ll want your own dice “just to feel them in your hand.” Then a second set because the colors are pretty. Then a 3D printer “for minis.” Then a professional microphone “to do voices properly.” Then miniature paints. Then terrain pieces. Then a red wizard’s hat imported from the US that you’ll earn by sorting someone’s 9,000-book library for four days of unpaid labor.

I’m not saying you need any of that. I’m saying that once you feel what this hobby offers, you’ll want to invest in it. That’s different from needing to.

The Supply Side Solution

My goal isn’t subtle: Train 10,000 Game Masters. Not “help” them or “encourage” them—train them, specifically and systematically, until they can run their first homebrewed adventure with confidence.

Why homebrewed? Because published adventures teach you to follow someone else’s story. Homebrewing teaches you to facilitate your own. Published modules are training wheels. Homebrewing is the actual bike.

I built a free course that takes about 40 minutes. It’s on YouTube at puttheplayerfirst.com/course —no subscription required, no email capture, no paywall. Watch it, do the exercises, and you’ll be ready. That’s not marketing speak. That’s the actual outcome.

Because here’s the truth: Every new Game Master exponentially grows the community. A player can introduce one friend at a time, maybe. A Game Master can bring in five, ten, twenty people per campaign. If I personally introduced 1,300 people to TTRPGs by running games, imagine what 10,000 trained GMs could do.

The math isn’t subtle. The mission isn’t subtle. We have a supply problem, and the solution is making more supply.

TLDR – Because You’ve Earned It

- Stop mistaking performance for participation—Level One roleplaying (pure intention) is as valid as Level Four (voice acting)

- You don’t need fancy gear, perfect voices, or system mastery to GM—if you can talk, you’re qualified

- The hobby costs exactly zero rupees unless you make it cost more, which you absolutely will because it’s worth it

- FARTS (Fight, Avoid, Research, Trick, Speak) covers 90% of player actions—prepare for these and you’re ready for anything

- Cultural authenticity isn’t a topping you add—it’s flour mixed into the dough until indistinguishable

- Beautiful props that constrain improvisation are worse than ugly props that enable it

- Every correction is a small violence that builds barriers—choose accessibility over accuracy

- Train more GMs and the community grows exponentially—one player brings one friend, one GM brings twenty

- Free doesn’t mean cheap—D&D’s SRD, one-page RPGs, and community resources offer complete experiences at zero cost

- The hobby should feel like escape, not examination—import wonder, not judgment

How This Connects to Serious Games (And Why It Matters)

I run PutThePlayerFirst.com, where I design serious games and simulations for leadership development. Every principle I’ve described here—accessibility over accuracy, facilitation over performance, removing barriers to entry—translates directly.

When I facilitate a leadership simulation for a corporate client, I’m not running a game. I’m creating a space where people can try on behaviors they’d never attempt in reality. The marketing manager who’s afraid to challenge authority? In the simulation, she’s a rebel leader making life-or-death decisions. The operations director who avoids conflict? He’s negotiating resource allocation with limited information and high stakes.

The moment someone feels judged for “playing wrong,” the magic circle breaks. They retreat into safe, predictable behavior. The simulation becomes theater—people performing what they think facilitators want to see rather than discovering what they’re capable of.

So I stopped correcting. Stopped performing. Started trusting that if I built the right constraints and asked the right questions, participants would teach themselves lessons I could never lecture into existence.

The washing machine incident taught me that authenticity matters more than precision. The Oppenheimer dungeon taught me that beautiful constraints are still constraints. And training 1,300 people to play TTRPGs taught me that reducing barriers—financial, social, performative—is the only way ideas spread.

Serious games work the same way. Build the right space. Remove the barriers. Trust people to surprise you. Then get out of the way and watch what happens when imagination has room to breathe.